“God does not play dice with the universe.” One of Albert Einstein’s most famous, and at the same time, one of his most misunderstood and misinterpreted phrases. One that had absolutely no relevance or reference to a so-called ‘destiny’, despite what it sounds like. A phrase that refers to one of physics’ most important theories – quantum mechanics. Or to be more specific, a phrase that expressed his discontent at the bizarre nature of quantum mechanics. And its suggestion of randomness and uncertainty – in what is a largely measurable and deterministic universe. Which makes it almost ironic that it was his own work that laid the foundation for the said theory. While evidence may not entirely support Einstein, Benjamin Labatut’s ‘When we cease to understand the world’ shows that man just might play dice with the universe.

When we cease to understand the world – Reality woven together with fiction

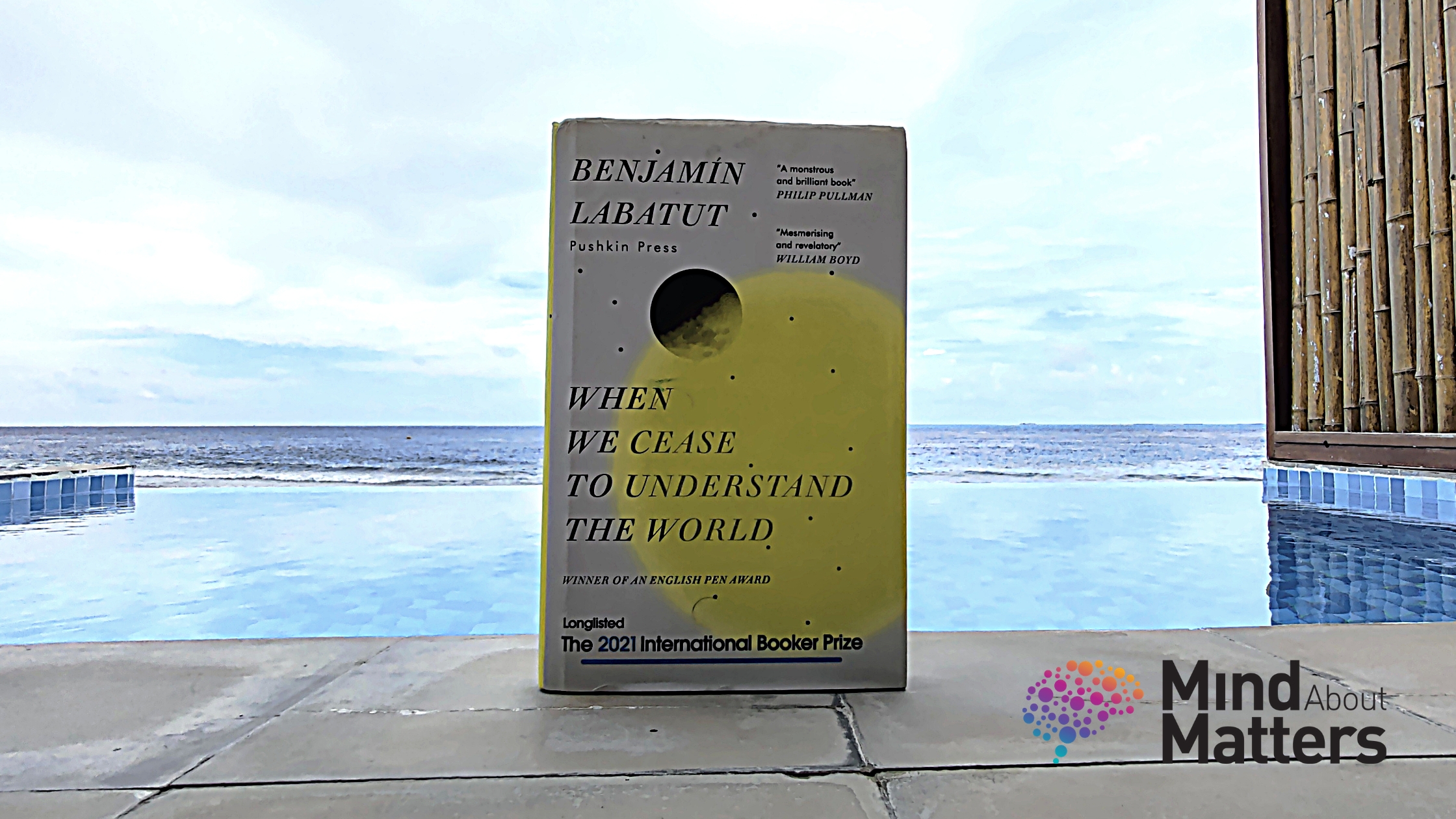

A non-fiction novel, ‘When we cease to understand the world’ brings to its narrative some of the world’s most renowned scientists interspersed with phases of incredible imagination. Written in a manner so absorbing that it’s often difficult to distinguish between facts and fiction. The stories of great minds stretching the boundaries of sanity, and venturing into and dangerous territories are what make this book as engaging as it is intense, dark, and even disturbing in some ways.

What’s adds to the intrigue is Labatut’s ability to stitch together a narrative that includes renowned personalities from the world of science – like Fritz Haber, Alexander Grothendieck, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrodinger, and others. Not as isolated individuals or chapters, but in the form of a story, seamlessly connected using figments of his own imagination. Almost like you’re reading a history of physics. For all its greatness, all its achievements, all its dark phases.

A story that can make you ask yourself, ‘What is the price of genius and discovery?’

The price of discovery

Starting off with the invention of a synthetic colour in the 18th century. To chemical warfare in World War I, to the use of Zyklon B in Nazi gas chambers. ‘When we cease to understand the world’ brings to life the stories of scientists, and their relentless pursuit of new discoveries in the world of physics. Stories that focus not just about their contributions to physics. But go into great detail to relive what seems almost a methodic descent into delusion.

Labatut’s narrative features a gallery of brilliant, but tormented minds. Including Karl Schwarzschild, an astronomer overcome by horror over his own discovery of singularity. Shinichi Mochikuzu and Alexander Grothendieck, mathematicians who solve seeming unsolvable problems, only to destroy their work and go into hiding. Alan Turing, the father of computing who poisoned himself. And Johann Jacob Diesbach, the inventor of a pigment that formed the basis of cyanide. And many more…

But the fact that Labatut’s stitches this narrative together with fiction is perhaps key to the opinion that this isn’t merely a book about science, its heroes, or their discoveries. But about the price that has to be paid for these discoveries. By the brilliant minds themselves. And the world at large. After all, it is discoveries made to expand the human mind, and universe that have led to some of the most devastating events history has witnessed. As Grothendieck said, ‘The atoms that tore Hiroshima and Nagasaki apart were split not by the greasy fingers of a general, but by a group of physicists armed with a fistful of equations.’

When we cease to understand the world – Does man play dice with the universe?

A thrilling opening to the book talks about Fritz Haber, who despite his role in the chemical warfare that took the lives of thousands of soldiers in World War 1, is more known for discovering a process that allowed Nitrogen to be harvested and used for making fertilizers. A discovery that has been responsible for saving millions of lives from famine, even earned him a Nobel prize. But one also that threw him deeper into guilt. Because his method he believed, had so altered the natural equilibrium of the planet that he feared the world’s future belonged not to mankind, but to plants.

We have reached the highest point of civilization. All that is left for us is to decay and fall.

Karl Schwarzschild

While countless have already paid the price for some of the most brilliant discoveries mankind has made, one question remains rife. Not just for physics or even science, but for all of civilization. Will present and future generations continue to pay the price of discovery? Will we learn from what has passed? Or will mankind continue to play dice with the universe? And if the events of the last two years are any indication – whether it is the Covid-19 outbreak or the violence in Ukraine, the answer is concerning, at the very least.

The Night gardener

Journeying through decades of scientific discoveries and the minds that conceived them, Labatut’s story ends with a what seems to be a completely fictitious character. The night gardener, who happens to be a former mathematician. One who speaks of mathematics in the same way a former alcoholic speaks about alcohol. Not for all the good it offers. But pain and suffering it has and continues to manifest. Irrespective of the intentions of mathematicians. The gardener’s belief and story reminds of something said in the movie Jurassic Park, ‘Scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they never stopped to think if they should.’

It was mathematics – not nuclear weapons, computers, biological warfare or our climate Armageddon – which was changing our world to the point where, in a couple of decades at most, we would simply not be able to grasp what being human really meant.

The Night Gardener

The last word – When we cease to understand the world

Shortlisted for the 2021 International Booker Prize and 2021 National Book Award for Translated Literature. And one read tells you why. Written at a breakneck pace, ‘When we cease to understand the world’ is an unusual hybrid between fact and fiction that uses infinite imagination and detailed facts to tell a story that itself is open to a multitude of interpretations. It’s a journey not into the unknown. But into a known that has the power to deliver unknown consequences. Giving us both, an insight and a warning into what is possible.

As Labatut himself puts it in words he credits to Schwarzschild, ‘Only a vision of the whole, like that of a saint, a madman or a mystic, will permit us to decipher the true organizing principles of the universe.’